While I am a pedant and have strong opinions on grammar, I usually don’t spend so much time on trite issues like this. But I awoke to my dog dry heaving at 2 a.m. and couldn’t get back to sleep. After reading on my Kindle for a while, I eventually gave in to scrolling social media and came across this post. I guess these are the thoughts that go through my sleep-deprived head when there’s nothing else to keep it occupied. The research paper in question is otherwise above my head but seems to be quite interesting and worth reading.

A tweet about decreases in muscle strength for aging women caught my eye.

Women experience faster, earlier muscle decline with age. New data from @steven_obryan and co. in women aged 18–80 found the steepest declines begin in the 4th decade, around menopause.

—@jacksonfyfe on X

Something about this felt off. While I understand that muscle growth slows in the late 20s and early 30s, surely accelerated muscle decline couldn’t be that early. And “around menopause”? Women who experience menopause in their 40s are considered early. But menopause in the 30s would be considered very unusual. Yet this tweet was suggesting that both were normal at this stage of life.

It became clear that the issue was confusion about ordinal nomenclature1 for decades.

This can often be tricky. Our first birthday is when we turn one, which happens at the end of our first year. Similarly, our 10th birthday is at the end of our tenth year. We are in the nth year before we turn n years old.

The same goes for decades. Our first decade is from birth until the end of our 10th year. Our 10th birthday is the start of our 2nd decade, which continues through our teens until we reach 20 years old, when we enter our 3rd decade, etc.2

I can’t blame someone for getting this wrong, but I wanted to make sure the research wasn’t revealing something more alarming. I fully expected the paper to either correctly identify the nominal decade or to simply report the years (e.g. 40–49).

I pulled up the paper, The contribution of age and sex hormones to female neuromuscular function across the adult lifespan to skim the abstract.

Voluntary and evoked torques and one-repetition maximum decreased non-linearly with age, with accelerated reductions starting during the fourth decade.

Uh oh.

From the Key Points section:

We show an accelerated reduction in neuromuscular function, primarily of peripheral muscular origin, that occurs during the fourth decade and coincides with menopause onset.

I continued reading, looking for any mention of the actual years.

From the Results section:

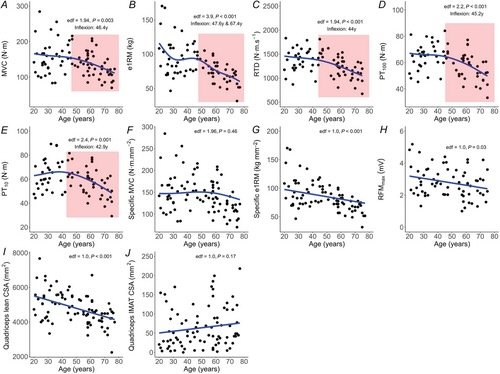

The steeper decline of each curve, defined as the point where the first derivative fell below 75% of its maximum value, started at 42.9 years of age for PT10, 44 years of age for RTD, 45.2 years of age for PT100, 46.4 years of age for MVC and 47.6 years of age for e1RM (Fig. 1A–E, red shaded region).

The accompanying chart highlights the areas of interest with age on the x-axes. Note that none of the highlighted sections go into the 30s. They all start in the 40s.

The 40s. Hmm, ok, the results were as I expected, but even the authors of the paper got the decade wrong.

How could this happen?

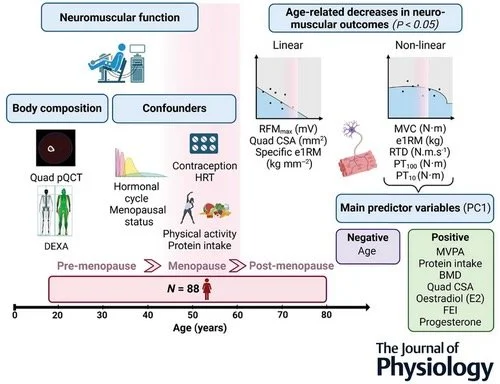

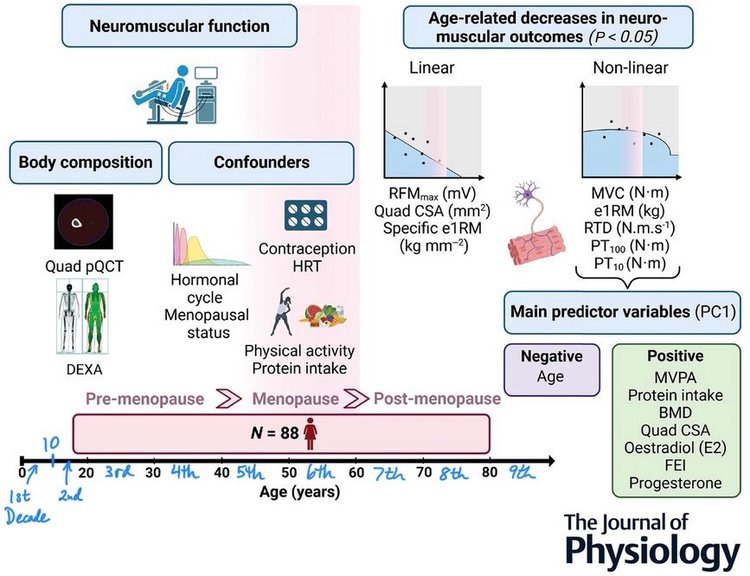

The original tweet and the paper include this graphic combining the various factors relating to muscle decline in women overlayed on a timeline depicting age.

AHA. There it is.

The timeline begins at zero with tick marks for every 10 years, except for the first 10. It starts at 0, skips to 20, then continues by 10s until 80 with the axis line ending in an arrow. The gap between 0 and 20 is conspicuously equal to the subsequent gaps—20 years were condensed into the same space as 10 years for the rest of the timeline.

This is a classic example of an axis-anchoring error in chart design.3 It usually is done on the y-axis of bar charts, either intentionally or unintentionally, to inflate the effect of smaller differences in values.

In this case, it may have played a role in selecting the wrong name for the decade starting in one’s 40s—the fifth decade.

-

Also called ordinal counting or naming. ↩︎

-

What’s curious to me is that most people get this right with centuries. The 19th century refers to any year starting with “18__”. We’re currently in the 21st century and will be until 2100 (or is it 2101?). ↩︎

-

Starting the axis at a number other than zero. I may have made up this term, but starting the axis at zero is a commonly accepted best practice. ↩︎